Reproductive tourism occurs when people travel to access such reproductive technologies and services as (i) IVF; (ii) sperm and egg donation, (iii) sex selection and embryonic diagnosis, and (iv) surrogate parenthood. It also includes the converse: (i) abortion; (ii) contraception; and even (iii) vasectomies.

Technological change has enabled many decisions over many possibilities, from ‘test-tube babies’ to ‘designer children’ (notably by sex), with cloning perhaps waiting in the wings.

Like most forms of human behavior, reproduction appears to be a private and intimate affair. Yet, it is bound up in national policies (for example, abortion, provision of contraception, family sizes, and one-child families). Partly in response, reproduction has ‘gone global’ through transnational adoption (recently involving prominent film and famous music stars), fertility treatment, and reproductive tourism in what has been described as a ‘global market of commercial fertility.’

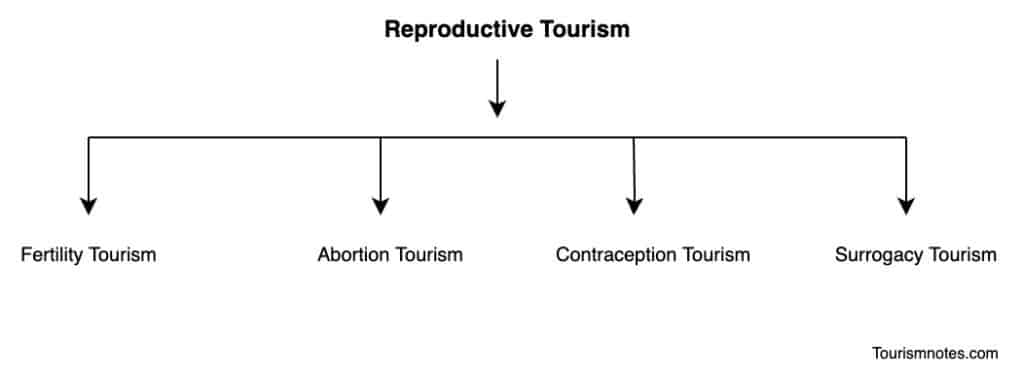

Types of Reproductive Tourism

Reproductive tourism may be divided into four types. These are followed as :

- Fertility Tourism

- Abortion Tourism

- Contraception Tourism

- Surrogacy Tourism

Fertility Tourism

‘Fertility tourism’ involves access to overseas reproductive technology, enables cheaper, more efficient, or comprehensive services, and bypasses restrictive regulations, long waiting lists, legal constraints, and some- times high costs.

Such ‘global fertility tourists’ have consequently been seen as ‘desperate to break free from financial, legal, and ethical constraints.

Fertility centers exist in several countries, from the USA and Israel to small island states such as Cyprus and Barbados. Unlike other contexts where major ethical principles occur, some standard tourist potential is apparent, and it has even been called a ‘procreation vacation.’

Israel is a leading fertility tourism destination for IVF, with the highest global ratio of fertility clinics per capita. Still, the USA and Spain attract many Europeans because of higher success rates and lenient regulations.

Patients travel from countries like Germany and Italy, which are very restrictive over the number of eggs which may be fertilized and the use of donor eggs, or from Canada, where it is illegal to pay donors for eggs or sperm, or from countries like Costa Rica where it is virtually impossible to obtain eggs.

Countries such as the UK and Sweden, which only permit non-anonymous sperm donors, have a shortage of donors and long waiting lists (as long as six years or more in the UK) and are more likely to be marketed overseas for IVF procedures.

Over 250 Swedish sperm recipients annually travel to Denmark for insemination, partly because the insemination of single women is permissible. Parents seeking a particular gender for their children tend to go to the USA; parents from Australia, where gender selection is illegal, mainly travel there and face a starting price of at least US$25,000.

Somewhat differently from most forms of medical tourism, fertility tourism is centered primarily within developed counties that are the primary sources and destinations, involving high costs and perhaps as many as 20,000 couples a year.

As the website of one Spanish clinic states: ‘The present law governing assisted reproduction in Spain allows treatments to be carried out here which are restricted in other countries’ Countries seeking to establish medical tourism have offered procedures that would not pass scrutiny in many contexts; thus Georgia permits methods that are banned in Europe: surrogate egg donation and a database of surrogate mothers with photographs, a practice that would breach privacy restrictions in many countries.

What is possible in particular countries varies considerably, and even within Europe, there are critical differences between states, while attempts at regional regulation have been unsuccessful. Germany imposes strict limitations on access to reproductive technologies, whereas Israel offers firm support, and Ireland has significant constraints on abortion. Belgium and Italy have little legislation on assisted reproduction and are popular destinations within Europe.

That Spain and Slovenia are both significant destinations for egg procurement indicates no necessary correlation between Catholicism and lack of reproductive support.

New reproductive technologies raise ethical questions around individual and state responses to liberty, rights, and autonomy. Diagnostic tools screening for genetic disorders or sex raises questions about eugenics, screening for disability, and gender inequalities.

Third-party reproduction, such as surrogacy and sperm, embryo and egg donation, raise additional questions over parental rights and the commodification of bodies and babies, which have not been resolved in national contexts where they are permissible, even without venturing across international borders and into different cultural terrains.

Access to IVF, abortion, and contraception also raise religious and moral questions over ‘unnatural’ procreation and its termination, with some parallels in stem cell therapy, and over who might have access to technology (such as same-sex couples, older people, or individuals without partners).

By offering distinctive procedures in demand, countries that have not otherwise gained from medical tourism, such as Georgia and Vietnam, have attracted some visitors. Ukraine has also become a minor player by offering IVF services to gay couples and single. Parents, while age is no barrier either there or in India, twins are born to an NRI couple resident in Britain with a combined age of 131.

Surrogacy Tourism

Surrogacy is primarily an Indian phenomenon. India has been seen as an ideal destination since Indian women rarely smoke and drink, and it more obviously offers ‘First World medical services at Third World prices. Accessing surrogate mothers in India assures the right of the intended parents to a supply of Asian donors, cheaper services, multiple embryo transfers, and sole parental rights, the last especially being impossible in home countries such as the UK or Australia.

Conversely, the surrogate parent has restricted rights, fewer than available in the source countries, in a high-risk context with perhaps limited economic gain and lost emotional attachments.

Commercial surrogacy has been legal in India since 2002, as it is in many countries, including the USA. Still, it has come closer there to being a viable industry rather than a rare fertility treatment’ so that ‘it could take off for the same reasons outsourcing in other industries has been successful: a wide labor pool working for relatively low rates in almost every large city, while prompting concern over ‘baby farms’ and ‘wombs for rent at meager cost, so transforming women into child-producing commodities.

Various Indian companies exist, some with evocative names such as ‘Babies and Us’ and ‘I wanna get pregnant”. At one small town in India, Anand (Gujarat), coincidentally known as ‘the milk capital of India,’ early in 2008, over 50 women, mostly poor villagers, were pregnant with the children of couples from the USA, Taiwan, Japan, Australia, the UK and elsewhere, at least some of whom were diasporic Indians.

Since then, surrogacy has expanded rapidly with an estimated 350 providers in India, some three times the number in 2005, enabling about a thousand attempts a year, a third from outside India.

Income generated from this in 2009 was estimated at as much as US$445 million. However, in 2010 the Australian government announced that it would not guarantee citizenship to surrogate babies born in India.

Australia Surrogacy, an MTC that organizes international surrogacy, stopped working in India because massive delays and citizenship requirements had become too onerous. Ethical issues merged with legal and constitutional questions to challenge the future of Indian surrogacy, at least in the case of Australia.

Surrogate mothers may earn significant sums, rising from about US$2500 in 2004 to over US$10,000, in big cities like New Delhi. Surrogate mothers in India make less than 10% of the overall expenditure on surrogacy, and their incomes are about 10% of those of surrogate mothers in countries like the USA.

However, surrogacy studies suggest that most surrogates are satisfied with their surrogacy experience, do not experience emotional attachments to the surrogate child, and feel generous about surrogacy even years afterward while earning incomes that are several times an average annual rural Indian wage.

Fears of surrogate mothers keeping babies have been unfounded. During surrogacy, women are usually given superior nutrition and medical care and housed in monitored circumstances to escape the stigma of surrogacy. Some women, however, may be forced into surrogacy by their husbands, and most volunteer only to escape grinding poverty.

Whether this will pose difficulties for some children who are visible of somewhat different ethnicity from their parents remains to be seen. Otherwise, debates over surrogacy parallel those over transplant tourism.

Despite the Indian focus, growing global complexities have emerged from the intricacies of surrogacy and reproduction:

Rudy Rupak, president of Planet Hospital, a California-based medical-tourism company, says that in the first eight months of this year, he sent 600 couples or single parents overseas for surrogacy, nearly three times the number in 2008 and up from just 33 in 2007.

All of the clients this year went to India except seven, who chose Panama. Most were from the U.S.; the rest came from Europe, the Middle East, and Asia, primarily Japan, Vietnam, Singapore, and Taiwan; because of growing demand from his clients for eggs from Caucasian women, he’s started to fly donors to India from the former Soviet republic of Georgia.

A Planet Hospital package that includes an Indian egg donor costs [US]$32,500, excluding transportation and hotel expenses for the intended parent or parents to travel to India. An egg package from a Georgian donor costs an extra [US]$5,000.

Even more complex global it is are evident. In 2007 a single Russian woman, a management consultant born in Pakistan, first sought to adopt a child in Germany, where she had citizenship. That was unsuccessful, and she moved to the UK to take advantage of the country’s more liberal attitude to single women who sought IVF.

After three years without success, she purchased sperm online from a Danish sperm bank retailing in New York, since purchasing in the UK would have involved a 3-year wait and considerable expense, and the sperm was used to fertilize the fresh eggs of an Indian woman in Mumbai. She was thus due to having a child of Danish- Indian genetic origin but knowing little of the two individual donors.

Abortion Tourism

Where abortion is illegal or carries a heavy social stigma, pregnant women may travel to countries where they can terminate their pregnancy, which is called ‘abortion tourism.’

Technological change has transformed the mechanics, location, and ethics of reproduction. With rare exceptions, such as Malta, throughout the northern hemisphere, abortion is legal in certain circumstances. Still, availability ranges from ‘on demand’ to severely constrained, as in the mainly Catholic nations of Ireland, Poland, and Mexico.

Thus Polish women seeking to escape restrictive abortion laws travel to Ukraine or Belarus to terminate pregnancies. However, higher-income women travel to nearby EU countries, such as the Czech Republic and Slovakia, or more expensive Germany, Belgium, and Austria.

However, in 2007 as many as 31,000 Polish women had abortions in the UK, reportedly a 30% jump from previous years, but some may have been residents in the UK.

Just as in other components of medical tourism, reliable statistics are not surprisingly unavailable, though it has been estimated that in 2007 approximately 200 women per week were traveling to the UK from Ireland and Northern Ireland and that in 2006 just one Spanish clinic near the Portuguese border saw 4000 Portuguese women come to terminate pregnancies.

Several Western European countries have been destinations for women seeking abortions, notably Sweden and Spain, with Barcelona described as ‘Europe’s abortion mecca,’ where people from much of the continent could evade restrictions on late-term abortions. Class and socioeconomic status influence the ability to migrate and gain access to safe abortions.

Mexican women traveling to the USA for abortions were typically well educated and wealthy, came from Mexico City and more prosperous states, did not have to cross the border illegally, and could avoid clandestine and self-induced procedures. Poor women in Mexico, Ireland, and Poland were often in a socio-economic position where they could neither migrate nor gain safe abortions.

While such mobility has been strongly criticized in source countries where it breaches widely held moral positions and national legislation, it has also been criticized in destination countries for both the negative connotations of ‘abortion tourism’ for national identity, as occurred in Spain in the late 2000s and the local costs.

In 2010 there was resentment in the UK of an advertising campaign by a pro-abortion group in Poland that mimicked a Mastercard advertisement and offered ‘For everything you pay less than an underground abortion in Poland.’

Resentment centered on the view that foreigners used medical tourism, in this and other forms, to take free advantage of the NHS, which was estimated to have cost it £200million a year, giving rise to a degree of moral panic over the ownership and use of national services.

Similar moral panics have occurred in places as diverse as Thailand, New Zealand, and Australia. In certain circumstances, therefore, particular variants of medical tourism have been seen as being at some cost to national populations in lost income or displacing local people rather than as a boost to the national economy.

In its distinctive form, ‘abortion tourism’ has clear parallels with other forms of medical tourism. The rich can afford to travel further for care, while the poor are least likely to travel or cross nearby borders and may face complications (of various kinds) from not gaining access to adequate or any services.

Destinations are thus governed by cost. Anonymity is also essential. However, abortion tourism is confined mainly to middle-income and developed countries and is unrelated to diasporic tourism.

Contraception Tourism

It is also called Birth control tourism. When women travel to seek treatment for birth control is called contraception or birth control tourism.

Contraception is globally more accessible than abortion, and moral objections to it are weaker and less widespread; however, though some techniques and supplies are unavailable in many countries, demand can be considerable.

Some MTCs thus advertise access to contraceptive services: Healthbase, in the USA, offers the implantation of intrauterine devices or their removal in Mexico, Costa Rica, or India.

‘Birth control tourism’ appears to have been described just once; where in the early 2000s, the Mayor of Manila issued a total ban on contraceptives, and urban residents had to move elsewhere in the Philippines for access. The extent of international travel for access to contraception or vasectomies is unknown, but it plays some part in overall medical tourism.